Bells and How They are Made

The Chinese had bells thousands of years ago, but they didn’t look much like modern bells. Some of then were forged from sheets of metal, a bit like giant cow bells.

Modern bells are are cast in a mould, and made of bell metal, which is a form of bronze, containing 23% tin and 77% copper. They have been made this way for hundreds of years. The shape gradually evolved to its present form, as founders experimented to find out what made a good sound. Compared with modern bells, mediaeval bells were longer and thinner.

Casting a bell

The mould is made in two separate parts, one shaped like the inside of the bell and one shaped like the outside.

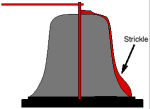

The core is built up around bricks on a base plate. The mixture used to make the mould contains many traditional materials, typically sand, loam, straw or horse manure and goat hair. The presence of fibres in the mould is important. They burn in contact with the molten bell metal, creating tiny tubes that help air to escape from the mould. The final shape is controlled by using a ’strickle’ - a wooden board shaped like the cross section of the bell to be cast. Rotating the strickle around the mould ensures that it is circular.

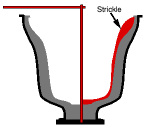

The cope, or outer mould, is formed with the same material, inside a large iron bell-shaped container. This strickle is used again to ensure the correct profile inside the mould.

When the moulds are dry they are clamped together ready for casting. After the molten metal has been poured in, it is left for several days (depending on size) to cool down before the mould is broken off. The bell is cleaned and to top is ground level to provide an accurate mounting surface.

Tuning the bell

A bell vibrates in several different ways at the same time, creating different 'partial frequencies' that depend on the shape and thickness of different parts of the bells. They are not directly related, unlike an organ pipe or a guitar string, which generates 'harmonics' related by precise numerical ratios. The shape of the bell has evolved so that the main partials are in roughly the right relationship. Removing small amounts of metal from different parts of the inside of the bell adjusts the different frequencies. A modern bell is cast deliberately thick, and then tuned on a vertical boring machine (a giant lathe). Before this, metal was chipped away with a tuning hammer, a practice that persisted into the early 20th century, despite the introduction of tuning machines from the late 18th century.

The science of modern bell tuning was only fully understood in the late 19th century, and is generally named after Canon Arthur B Simpson who first described it. All UK founders subsequently adopted 'Simpson tuning', which controls five frequencies. Tuning is a complex process though, because each location affects more than one of the frequencies, so despite all the science, it still depends on skill and judgement. The table below shows the five main partials that are tuned.

PartialFrequency ratioMusical interval Hum0.5Octave below Prime1 Tierce1.2Minor third Quint1.5Fifth Nominal2Octave above See a comparison between

old and new tuning of All Saints bells .

Bell foundries

Of more than 170 foundries known to have operated over the centuries in Britain, only 8 were still in business by 1900, and six of those have since closed. Their dates of closure are: Shaw (Bradford) 1902, Blackbourne (Salisbury) 1903, Warner (London) 1924, Aggett (Chagford) 1926, Gillet & Johnston (Croydon) 1948, Bowell (Ipswich) 1950. Only two UK bell founders remain:

John Taylor Bell Founders in Loughborough and

Whitechapel Bellfoundry in London. The

Wokingham Bellfoundry operated from around 1350 until 1622.

Click here to see how the number of UK bell founders has grown and shrunk over the last 1000 years.